I just finished Misreading Scripture with Western Eyes this morning which is a very good and very readable book chronicling some of the ways that a western worldview affects our preunderstandings about scripture.

In the conclusion of the book, the authors made an observation that surprised me. American Christians are often impressed by the genuine community enjoyed by Asian Christians in places like South Korea. While Korean Christians "applaud American Christians for generosity and forgiveness.." I guess according to certain metrics Americans could be classified as generous. We have a long way to go if we are going to model biblical generosity, but Americans and American Christians specifically are a giving bunch. You may disagree, which is fine. But this post isn't really about American generosity.

This post is about the second part of that observation. Are we really a forgiving culture? Because so many of us are inclined to think the worst about our culture, our knee-jerk answer would be to answer negatively. Of course we aren't a forgiving culture! (These people would probably also be the first to protest that we are not a generous culture either.) As I think about it, however, it strikes me that we are a forgiving culture in general. As with generosity, we have a long way to go to model biblical forgiveness. We are far too often arrogant and patronizing or impulsive and violent. But I think that we are (relatively speaking of course) a forgiving bunch of people.

If you are tempted to disagree with me, I would point out that yesterday was December 7. A day that continues to live in infamy but not a day that lives in hatred or animosity. You read and saw a lot of remembrances of the awful events of Pearl Harbor. But what you didn't see were angry rallies against the Japanese people or mobs burning Japanese flags. I don't want to trivialize the complicated history that has happened since 1941, but for the most part, we have forgiven Japan and the Japanese for Pearl Harbor.

The authors of the book argue that the individualism that is characteristic of American culture actually has helped us to be a more forgiving people. It's an interesting thought. We are undoubtedly individualists - in our politics, in our economics, in our careers, in our families, and in our religion. We think of guilt as being personal, not collective. Therefore, we have come to see issues of salvation and forgiveness as also being personal. When Jesus says that God loved the world so much that he sent his son, we may hear "world" but we think "me." We talk of having a relationship with God through Christ, but we understand that relationship in purely individualistic terms. Jesus loves us all, but he loves us as individuals. This is a reason why so many western Christians struggle with the household conversion texts of Acts and the generational sin texts of Deuteronomy. We are each responsible for our own sin and salvation, aren't we? And our ecclesiology struggles under the weight of our individualism. The church exists for me, and for you, but most importantly, for me. I find myself typically struggling against this tendency in myself (and often failing!) and preaching against it in others. And for good reason. I don't think our individualism is biblical. Not only that, it isn't even "normal." Individualism has certainly been a minority position through history and still is in the world today.

But still...Might this individualism help us to forgive? Because we view sin and salvation as personal, we are not inclined to hold others responsible for something that they did not directly do. We are much less likely to feel lasting anger for a sin committed against someone not directly connected to us (usually in America that means only your immediate family). We find it highly unusual when someone apologizes for something that they didn't do. Added to this, we are not an honor/shame culture either. We get angry when someone hurts us, dismisses us, or treads on our freedom. We are not nearly as concerned about public honor and shame as most people around the world.

Most Americans today do not feel a direct impact by the events of Pearl Harbor. We don't feel the sting of shame or injustice. Our experience with the Japanese is completely different than our grandparents. We've moved on. We've bought their cars and their electronics. Americans also recognize that most Japanese today weren't alive during World War II. Why would we hold them accountable for their grandparents' sins? Pearl Harbor was treacherous. But it was a treachery committed by people two generations ago against our grandparents or great-grandparents. When our grandparents do say something awful against the "Japs" it shocks us. They were directly impacted. We were not. It is not in our culture to hold generational grudges against a people.

Some might bring up the events of September 11 as a counter-argument. It sure seems as if Americans are holding an entire group of people (Muslims) guilty for this act of treachery. But this actually helps to prove my point. Are there pockets of anti-Muslim sentiment in our nation? Of course! But we have heard almost from the day of the attacks the constant refrain that this was attack was perpetrated by individuals NOT by a people. I would argue that Americans as a whole have gone out of their way since September 11 to show their love for Muslim people.

Forgiveness is always difficult. But it is even more difficult in a collective, honor/shame culture. You must learn to forgive not just those who have shamed you but also those who have shamed your people. And not just those who happen to be alive today, but those going back generations. When Jesus tells us to love our enemies, most of us think of an individual - my enemy. Jesus' original audience did not. They thought of "our enemies." So perhaps we have found at least one area where our individualism might help us.

What do you think? Do you think that we are a forgiving culture? If so, is this related at all to our individualism?

This blog is designed as a resource for the student of biblical interpretation. Relevant quotes and bibliographic information is provided on a broad range of topics related to the study of biblical interpretation. As a blog, this site will always be a work in progress. Feel free to search through the archives, make comments, make ammendments, or suggest relevant content to add to this blog.

Sunday, December 8, 2013

Thursday, November 7, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 7)

This the final part of the series. The purpose of this series was to help myself and my students and whoever might also read this blog to think about how we talk and debate about difficult issues in the church. This is not something that we always do very well. Some would rather not talk about difficult issues at all. Others enjoy arguing about difficult issues a little too much. I just think that we have to do a better job in this area. There are so many difficult issues that need some sort of principled position from the follower of Jesus. But how do we approach these issues in ways that honor the message of the Gospel? This series has been a small attempt to try and answer this question.

You can read the other posts here.

Part 1: Have I loved the person on the other side ofthis issue?

Part 2: Have I done my exegetical homework?

Part 3: Have I studied the opinions of the church bothpast and present?

Part 4: Have I clearly identified and defined the issue?

Part 5: Have I employed sound critical reasoning skills?

Part 6: Have I taken the time to understand the otherside of this issue?

Part 7: Have I humbled myself (and my tradition) enough to listen?

You can read the other posts here.

Part 1: Have I loved the person on the other side ofthis issue?

Part 2: Have I done my exegetical homework?

Part 3: Have I studied the opinions of the church bothpast and present?

Part 4: Have I clearly identified and defined the issue?

Part 5: Have I employed sound critical reasoning skills?

Part 6: Have I taken the time to understand the otherside of this issue?

Part 7: Have I humbled myself (and my tradition) enough to listen?

One of my

mentors in ministry was Dr. Robert Lowery at Lincoln Christian Seminary. I had

several classes in New Testament studies with Dr. Lowery, and in virtually

every class he would drill into his students that the most important principle

for biblical interpretation is humility. I teach in a place where it has been

standard to say that “context is king.” While I understand the sentiment,

context is certainly very important in biblical interpretation, I strongly

disagree. Biblical study of any kind must begin with a basic choice. Will I

listen to the Word or will I dictate to the Word? Will I submit or won’t I?

This is part of what James was getting at in James 1 when he said that we

should humbly accept the word planted in us which can save us. Such a humble

approach leads us to be doers of the word rather than just hearers.

I can be an

expert in the Greek and Hebrew languages, I can study the history and culture

of first century Palestine and the Roman world, I can take note of the smallest

point of syntax and grammar, I can be sensitive to the distinctiveness in

genres and figures of speech, and indeed I can be a master at recognizing the

importance of literary context both immediate and canonical – but if I don’t

have humility I will continue to see only what I want to see and hear only what

I want to hear in the text. Context doesn’t heal the human heart and fix our

pride. Lest we become too mechanical and scientific, we should remember Paul’s

exhortation in 1 Corinthians 2 that spiritual things are spiritually discerned.

This doesn’t happen until we have humbled ourselves and have resolved to listen

to the word of God in the text.

Sometimes my

students roll their eyes because they hear it so much, but I still carry on Dr.

Lowery’s legacy in my classes. The most important and first principle in

interpretation is humility. Never is this more important than when it comes

time to take a stand on a difficult issue. Too many times Christians will debate

from an ideological position rather than a sound exegetical position. There is

not an honest attempt to understand or explain an issue. There is only the

attempt to win an argument and score points with our constituency. We are

sometimes bad about constructing “shibboleth” type tests (Judges 12:5-6) to

decide who’s in and who’s out rather than humbly and honestly engaging an

issue. “What is your interpretation of Genesis 1 and 2?” “What is your position

on inerrancy?” “What do you believe about baptism or the Millennium or glossolalia?”

“Do you interpret Revelation literally?” Questions like these are too often not

an invitation to a discussion or even a debate. Instead they are traps designed

to see if you are safe or orthodox or “one of us.” It’s not really helpful or

honest.

When discussing

a difficult issue, we must learn to navigate the difficult terrain between

rigid dogmatism and non-committal openness. We must choose to stand somewhere

on difficult issues. (And some issues are of such importance that we must take a clear and public stand.) We

should not be so afraid of being wrong or corrected that we never say anything

at all. This is false humility. But at the same time, we should be humble

enough to be willing to change or nuance our position over time. A person who

has every issue resolved in their own mind either has a very closed and

arrogant mind or hasn’t thought enough about the issue.

Tuesday, November 5, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 6)

Have I taken the time to understand the other

side of this issue?

You are not

ready to debate any issue until you have honestly studied the arguments to be

made on the other side of the issue. For instance, if you firmly believe that

women should indeed be preaching ministers in local congregations, have you

studied and learned the arguments that are made by those who disagree? If you

passionately feel that pacifists have missed the point of the gospel and are

distorting New Testament ethics, have you taken the time to listen to the

arguments to be made in favor of pacifism? Learning the other side of any issue

will help in several ways: 1) You will make more intelligent arguments because

you have learned to spot the flaws in your own argumentation. Some arguments

only sound good from one side. The best arguments resonate with both sides. 2)

You will avoid various common fallacies – especially the straw man – because

you have allowed people on the other side of the issue to speak for themselves.

3) You will learn the various nuances in the issue. A non-researched point of

view will tend to see everything in very stark, black or white terms. 4) You will be a more compassionate debater.

Let me also

make a few specific suggestions in this area:

a. Am

I seeing this issue from the same perspective as the person on the other side?

Transactional

Analysis is used by some in the field of psychology to describe the

interactions between people in different ego-states. Transactional analysis is

based upon the idea that there are three different ego states within the mind

of every person. Those ego states are

called, parent, adult, and child. Smooth

communication continues between two people as long as they have complimentary

transactions. A complimentary

transaction is any transaction where the communication is parallel, i.e.

agreement on the ego states that are doing the communicating. Any time there is a crossed transaction, then

communication stops and problems begin.

This is because there is no agreement on the ego states of the sender and

receiver.

What this means

for biblical interpretation is that some people will interact with an issue in

a relational way. Some will interact in a practical way. While others will come

at the issue in a principled way. This causes considerable difficulty in our

discussions on various issues. This chart illustrates the idea with the issue

of divorce, but in the future we will see this play a large role in how we talk

about the issue of homosexuality. Younger people are making decisions on the

issue on the basis of relationship. Older people who grew up in a very

different culture are making decisions based on scriptural principle. Pastors,

on the other hand, have to think more practically. What are we going to do

about homosexuality in our community and our church? What I am advocating is

that before we enter into a debate on any issue, we should take some time to

reflect on how the other person is seeing this issue. They may in fact agree

with us in principle, but they aren’t necessarily concerned about principle as

much as they are concerned about relationships. That will change the way that I

go about talking about the issue.

Theological

|

Ecclesiastical

|

Personal

|

Parent

|

Adult

|

Child

|

Values/Principles/Idealistic

|

Responsibilities/Laws/Practical

|

Relational/Realistic

|

Divorce: God intended for one man and one woman to

be married for life (Gen. 2:24; Mark 10:6-9).

The Christian must always seek to uphold and live by God’s standard

and not man’s or the world’s.

Regardless of personal feelings or experience, the Word of God must

prevail and decide on all ethical issues, and especially that of marriage and

divorce (Deut. 12:32; Ps. 19:7-11; 119:9-11; Is. 55:8-9; Jer. 23:25-29)

|

Divorce: The Church must uphold God’s

standards in all areas, especially in the area of marriage and divorce. It needs to teach it and practice it. The church needs to protect and build

strong marriages and families (Eph. 5:22-6:4; Col. 3:18-21)

|

Divorce: Repent of any sin pertaining

to a divorce and to receive the forgiveness of God. The divorced need compassion, love,

understanding and acceptance from the church.

|

b. Is

the person on the other side of this issue from inside the camp or outside the

camp?

Paul didn’t

talk to people within his community in the same ways that he talked to people

from outside (compare his speeches at Lystra and Athens to his speeches to

Pisidian Antioch and the Ephesian elders in Acts). Jesus didn’t talk to people

within his community in the same ways that he talked to people who were on the

margins or who were outside the community (compare what he said to the religious

leaders to what he said to the tax collectors and sinners). There are certain arguments

that I would make with another Christian that I would never make with a

non-Christian person. This is especially true about the way I use scripture. For

instance, I shouldn’t expect a non-Christian person to care about or submit to what

scripture says (unless they are trying to distort scripture for their

argument). On the other hand, I probably should expect a person who calls himself

a Christian to in some way submit to the message of scripture. A debate with a

Christian is much more likely to deal with exegesis. A debate with a

non-Christian is much more likely to deal with issues of worldview.

c. Have

I studied the non-biblical side of this issue?

Should a

Christian support or oppose embryonic stem cell research? It is a good question

worthy of discussion. However, if a Christian is to discuss or debate this

issue, it is important that we have at least a foundational knowledge of the

science behind the issue. If we are debating homosexuality, we should be

familiar with the various non-biblical arguments (from genetics, psychology,

etc.) that are made supporting homosexuality. This doesn’t mean that we have to

be an expert before weighing in on any issue. This seems to commit another

fallacy which I call the expert fallacy – you must never talk about an issue

until you have mastered it and all the supporting research. If this were the

case we would never be able to talk about any issue. What I am arguing for

however is that we do take the time to listen to and explore the non-biblical

sides of these issues. It is not enough just to know the Bible.

Logical Fallacies

This was passed along to me by a friend. A pretty good summary of logical fallacies. Christians, if they are to debate and debate well, need to take these warnings to heart.

https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/pdf/LogicalFallaciesInfographic_A3.pdf

https://yourlogicalfallacyis.com/pdf/LogicalFallaciesInfographic_A3.pdf

Monday, October 21, 2013

Investing Money Bible Code (aka How to use the Bible to support your idolatry)

And Jesus said, "He who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice is like a wise man who invested heavily in gold and avoided European stocks like a plague. Also, Merica."

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 5)

It's been a while, but here is the fifth question to ask when taking a principled stand on a difficult issue of interpretation.

Have I employed sound critical reasoning skills?

Difficult issues don’t just require diligent study of texts; they also require sound, critical reasoning skills. Too often, in our haste to settle a dispute or a debate on a difficult issue we employ lazy and inflammatory rhetoric. Christians are often guilty of loving rhetoric too much and reasoning too little. Such rhetoric is not only unfair to the person on the other side of the issue. It is also unfair to the issue itself and hinders our ability to make principled and informed stands on the issue. Here are some of the most common fallacies in critical thinking that are made when debating difficult issues. I will illustrate with the issue of pacifism:

There are likely other fallacies that could be added to the list, but hopefully the point has been made. When Christians debate issues of difficulty – whether it’s pacifism or some other hot button issue – we do not argue the way that the talking heads on CNN or Fox News argue. Instead, we use sound critical reasoning skills in order to faithfully represent the issue at hand and those who are involved in the debate. I have committed too many of these fallacies myself, and I have learned the hard way that even though it might make you feel good in the moment to rattle off some grand, clinching statement any debate won with faulty logic will inevitably be a shallow victory. It is the Golden Rule of debating. Debate with others in ways that you would have them debate with you.

If you'd like some more information on logical fallacies in theological arguments, see the instructional video below.

Have I employed sound critical reasoning skills?

Difficult issues don’t just require diligent study of texts; they also require sound, critical reasoning skills. Too often, in our haste to settle a dispute or a debate on a difficult issue we employ lazy and inflammatory rhetoric. Christians are often guilty of loving rhetoric too much and reasoning too little. Such rhetoric is not only unfair to the person on the other side of the issue. It is also unfair to the issue itself and hinders our ability to make principled and informed stands on the issue. Here are some of the most common fallacies in critical thinking that are made when debating difficult issues. I will illustrate with the issue of pacifism:

a. Making

hasty or unwarranted generalizations: Jesus said to turn the other cheek.

Therefore he is calling all of his followers to pacifism.

b. Begging

the Question: Jesus was obviously a pacifist.

c. Either/or

Fallacy: Either you are a pacifist or you are militant.

d. Ad

hominem: Pacifists are just cowards.

e. Straw

man argument: Pacifists are simply passive about injustices which are being

committed.

f.

Ad populum: Most people in the church are not

pacifists, therefore pacifism is probably wrong.

There are likely other fallacies that could be added to the list, but hopefully the point has been made. When Christians debate issues of difficulty – whether it’s pacifism or some other hot button issue – we do not argue the way that the talking heads on CNN or Fox News argue. Instead, we use sound critical reasoning skills in order to faithfully represent the issue at hand and those who are involved in the debate. I have committed too many of these fallacies myself, and I have learned the hard way that even though it might make you feel good in the moment to rattle off some grand, clinching statement any debate won with faulty logic will inevitably be a shallow victory. It is the Golden Rule of debating. Debate with others in ways that you would have them debate with you.

If you'd like some more information on logical fallacies in theological arguments, see the instructional video below.

Thursday, October 3, 2013

Intelligent people drink pop

Semantics has always been an important part of the discipline of hermeneutics. In short, what did words mean as used by their authors/speakers in their original context? Our tendency is to see words as empty vessels which we feel free to fill up with our own meaning. Many anachronistic interpretations make this exact mistake. We see a biblical author use words like "love" or "hate" or "servant" and our inclination is to understand those words through a contemporary lens.

Good interpretation must acknowledge the fluidity of language. Word meanings are always changing. And word meanings are always deeply contextual - both literary and cultural. This slipperiness of language is well illustrated by the maps in the link below. Americans can't even agree what to call certain things or how to pronounce certain words and we all supposedly speak the same language. Our difficulties are compounded then when we are reading an ancient text originally written in a language and a culture very different than our own. This is one reason why the study of original languages (or at least the listening to those who have studied the original languages) is such an important part to Bible study.

22 Maps That Show The Deepest Linguistic Conflicts In America - Business Insider

Good interpretation must acknowledge the fluidity of language. Word meanings are always changing. And word meanings are always deeply contextual - both literary and cultural. This slipperiness of language is well illustrated by the maps in the link below. Americans can't even agree what to call certain things or how to pronounce certain words and we all supposedly speak the same language. Our difficulties are compounded then when we are reading an ancient text originally written in a language and a culture very different than our own. This is one reason why the study of original languages (or at least the listening to those who have studied the original languages) is such an important part to Bible study.

22 Maps That Show The Deepest Linguistic Conflicts In America - Business Insider

Monday, September 16, 2013

Sunday, September 15, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 4)

Have I clearly identified and defined the issue?

Before taking a

stand on any difficult issue, it is essential that we take some time to clearly

understand and define the issue. It might be good to answer these questions:

a. Is this issue an essential? In the

Restoration Movement, we have always operated under the slogan: “In essentials

unity, in opinions liberty, and in all things love.” This slogan isn’t of

course unique to the Restoration Movement. There is wisdom in this principle.

There are such things as essentials and opinions in theology, and it is

important to know the difference between the two. We don’t have the same

disposition towards essentials and opinions. There is a flexibility and freedom

in opinions that doesn’t necessarily exist in the essentials of the faith. This

principle also highlights the superiority of love in all things. But like all

principles, this one has within it a major flaw. What exactly counts as an

essential or an opinion? And who gets to decide? Some groups see adult immersion

as an essential. Some groups see glossolalia as essential. Some groups see

dispensational eschatology as an essential. Others see specific church

governance structures as essential. The only point that I wish to make here is

that when we are taking a stand on any issue we should pause to ask ourselves, “How

essential is this issue to me?” and “How essential is this issue to others?”

Maybe I could phrase it another way: How willing are you to damn another over

this issue? And if an issue is an essential to you, can you justify that

position? There are certainly issues that are this important, but I would

humbly suggest that these issues are relatively few. Most issues that we will

have to take a stand on fall into the category of opinion. Don’t get me wrong

though. Just because it is an opinion does not mean that we shouldn’t have an

opinion – even a strong, passionate one. But it does mean that we should have

more charity with opposing views.

b. Does this issue involve a principle or a

practice? Some passages teach principles. They are broad in their scope and

application. Some passages, on the other hand teach specific practices in

specific contexts. Maybe the best example of this involves the role of women in

the Church. Galatians 3 teaches a broad principle. When Paul says that within

the Church there is neither male nor female he is saying nothing about

day-to-day ministry within particular congregations. This is one phrase among

several in this text which is stating a broad principle of unity and equality

within the family of faith. In 1 Corinthians 14 however he restricts the role

of women within that particular congregation. This text is focused on practice

and application. It is narrower in its intent than Galatians 3. Many debates

are the consequence of one side arguing a principle (“Women and men are equal.”)

and the other side arguing a practice (“Women and men, while equal, do

different things within the church.”).

c. Is this a good/better issue? May

Christians watch R rated movies? May Christians drink alcohol or smoke cigars?

May Christians go to casinos? These types of ethical questions cause no end of

debates between Christians. Some would argue on the side of freedom. Some

others would argue on the side of righteousness. One side would accuse the

other of legalism. The other side would respond with accusations of cheap grace

and self-indulgence. I would argue that

usually these debates are framed up in the wrong way. We talk about these

things as good or bad, right or wrong. It may be more constructive to talk

about them as wise or foolish. This seems to be the approach that Paul uses

with the Corinthian church. Certain things may be permissible, but are they beneficial?

d. Is this issue implicit or explicit? There

is not a verse in the Bible that explicitly forbids abortion. There is not a

verse in the Bible that explicitly forbids the institution of slavery. In fact,

some passages seem to support the institution. There are some issues that are

only implicit in scripture. Implicit issues require that we understand how the

Bible creates a sort of “hermeneutical

trajectory” for many issues. For instance, the Bible doesn’t forbid

abortion. But the Bible does establish that all people have been created in God’s

image and are precious to Him. The Bible does establish principles of justice

especially for the vulnerable and the weak. The Bible also forbids murder. Based

on these clear teachings of scripture, we can discern a trajectory that when

read in our day would forbid the practice of abortion.

e. How are key terms being defined? I have

a good friend who begins virtually every theological discussion with the

question “What do you mean by that?” We occasionally give him a hard time about

it, but it is actually a very good question to ask. There are so many times

where two people will be discussing an issue being totally oblivious to the

fact that they are defining the terms completely differently. For instance,

when I say “pacifism” what comes to your mind? How would you define it? Chances

are good that your definition may be completely different than the definition

of someone else. Definitions matter. If we are going to take a stand on

difficult issues, we have to take care to understand the way that we are using

key terms. Pause to ask the question, “What do you mean by that?” You may also

want to pause and ask yourself the question, “What do I mean by that?”

Part 3

Part 2

Part 1

Part 3

Part 2

Part 1

Thursday, August 1, 2013

Tuesday, June 11, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 3)

Have I studied the opinions of the church both

past and present?

The Bible is a community book. It is a revelation that we share with one another. It is revelation that we share with the community of faith past, present, and future. Modernity has given us the philosophy that our own human reason is enough for discovering truth in scripture. Technology has made such a philosophy practical. And pietism has provided a spiritual justification for such individualistic approaches to the text.

The reality however is that scripture was never intended for mere private consumption. Do I believe in the virtue of individual study of the text? Yes. Certainly. But do I believe in the privatization of the text and studying the text in isolation? No. The Bible is and always has been the word that shapes our community as believers. Our New Testament was originally received through the ears as it was read publicly among the Church.

This has some important implications for us when it comes to navigating difficult theological/hermeneutical issues. Augustine (among many others) argued strongly for what is known as the “rule of faith.” This rule of faith (regula fidei) is closely associated with the T word – tradition. When we come across a text that is difficult to understand or an issue that is tough to figure out, Augustine advocated looking back on what has traditionally been taught in the tradition of the Church.

We modern evangelicals don’t much care for tradition. It’s a word that makes us feel constricted. (“What about freedom?”) It’s a word that we too often associate with “backwardness.” (“What about relevance?”) And to an extent, we are correct. Tradition has oftentimes been appallingly wrong. Those who preached indulgences in the late Middle Ages and those who preached segregation in more recent times come to mind. There have clearly been times where tradition has become more important than the clear teaching of scripture. But to shut the door on tradition altogether seems to me to be very unwise and extremely arrogant. It smacks of the type of generational prejudice that says, “We have got it all figured out. We would never make the types of embarrassing errors made by generations past. All of human history has been anxiously awaiting the wisdom and insight of our generation. You’re welcome!” (I’ve seen the same people turn into young curmudgeons as soon as they start to get passed by the next generation who obviously don’t know anything about anything.)

In light of this, I want to offer this suggestion. When taking a stand on any difficult issue, we should pause and ask, “How has this been handled by the Church historically?” This probably shouldn’t be our first question, but it definitely should be one of the questions we ask. There may be some insight to be gained from looking at 2,000 years of church history.

On a related note, I would also suggest that you should seek out expert opinions on issues from Christians in your own day (particularly Christians who might be outside of your immediate heritage). There are experts who have dedicated substantial time and effort to studying virtually any issue that we might have to deal with. Draw from their insight as they have struggled with the text.

The Bible is a community book. Interpretation does not begin and end with you. And further, let’s get rid of this pietistic error that essentially teaches that the Holy Spirit only (or principally) works on an individual level. The Holy Spirit is active in Christians everywhere and through all times. It could be that the Holy Spirit wants to teach us through the insights of others.

Part 1

Part 2

The Bible is a community book. It is a revelation that we share with one another. It is revelation that we share with the community of faith past, present, and future. Modernity has given us the philosophy that our own human reason is enough for discovering truth in scripture. Technology has made such a philosophy practical. And pietism has provided a spiritual justification for such individualistic approaches to the text.

The reality however is that scripture was never intended for mere private consumption. Do I believe in the virtue of individual study of the text? Yes. Certainly. But do I believe in the privatization of the text and studying the text in isolation? No. The Bible is and always has been the word that shapes our community as believers. Our New Testament was originally received through the ears as it was read publicly among the Church.

This has some important implications for us when it comes to navigating difficult theological/hermeneutical issues. Augustine (among many others) argued strongly for what is known as the “rule of faith.” This rule of faith (regula fidei) is closely associated with the T word – tradition. When we come across a text that is difficult to understand or an issue that is tough to figure out, Augustine advocated looking back on what has traditionally been taught in the tradition of the Church.

We modern evangelicals don’t much care for tradition. It’s a word that makes us feel constricted. (“What about freedom?”) It’s a word that we too often associate with “backwardness.” (“What about relevance?”) And to an extent, we are correct. Tradition has oftentimes been appallingly wrong. Those who preached indulgences in the late Middle Ages and those who preached segregation in more recent times come to mind. There have clearly been times where tradition has become more important than the clear teaching of scripture. But to shut the door on tradition altogether seems to me to be very unwise and extremely arrogant. It smacks of the type of generational prejudice that says, “We have got it all figured out. We would never make the types of embarrassing errors made by generations past. All of human history has been anxiously awaiting the wisdom and insight of our generation. You’re welcome!” (I’ve seen the same people turn into young curmudgeons as soon as they start to get passed by the next generation who obviously don’t know anything about anything.)

In light of this, I want to offer this suggestion. When taking a stand on any difficult issue, we should pause and ask, “How has this been handled by the Church historically?” This probably shouldn’t be our first question, but it definitely should be one of the questions we ask. There may be some insight to be gained from looking at 2,000 years of church history.

On a related note, I would also suggest that you should seek out expert opinions on issues from Christians in your own day (particularly Christians who might be outside of your immediate heritage). There are experts who have dedicated substantial time and effort to studying virtually any issue that we might have to deal with. Draw from their insight as they have struggled with the text.

The Bible is a community book. Interpretation does not begin and end with you. And further, let’s get rid of this pietistic error that essentially teaches that the Holy Spirit only (or principally) works on an individual level. The Holy Spirit is active in Christians everywhere and through all times. It could be that the Holy Spirit wants to teach us through the insights of others.

Part 1

Part 2

Sunday, June 2, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (part 2)

A couple of weeks ago I began this series of posts about how to take a stand on difficult issues related to scripture and interpretation. You can see my first post here. This is my second guiding principle.

Have I done my exegetical homework?

The belief in the perspicuity of scripture has long been treasured in Protestantism. You could make a case that this doctrine is one of the key convictions that eventually gave birth to the Protestant Reformation. It is the belief in the fundamental clarity of scripture. The Bible is able to be clearly understood by all people (although Luther and especially Calvin would hasten to add that the Holy Spirit must be involved in the process of reading in order to overcome the reader’s sinful nature). The belief in perspicuity moved the locus of authority in interpretation away from sacred tradition and the Church to the individual interpreter. Now Protestants, and especially evangelical Protestants, simply assume that the individual reading scripture on her own is perfectly capable and even expected to understand, meditate upon, and apply that scripture to her life usually within the parameters of a “daily quiet time.”

This isn’t the place to debate the nuances of perspicuity. I accept a certain level of perspicuity as being in line with the original intent of scripture. I believe that scripture is not just for the elites but is for all people in all times and places. However, even champions of the doctrine like Luther clearly believed that not every individual reading of the text was equally correct. There was an essential role for an informed teaching ministry within the community of believers to correct and to train in the proper meaning of scripture.

The reason that I am mentioning this point now is because I have noticed that when it comes to dealing with difficult issues in the text the doctrine of perspicuity is sometimes abused. For instance, take the issue of women’s roles in ministry. This is clearly a difficult issue that the church has been struggling with for years. Exegetically there are a small number of texts in the New Testament that seem to prohibit certain roles for women within the assembly of believers (specifically 1 Cor. 14 and 1 Timothy 2). If we are to ever arrive at a principled position on the role of women in ministry today, these texts have to be studied and “figured out.” There are all sorts of exegetical questions that we have to answer:

If we are to take a stand on a difficult issue like women’s roles in ministry (or dozens of other similar issues), we must commit ourselves to understanding the word by doing the difficult work of exegesis.

Have I done my exegetical homework?

The belief in the perspicuity of scripture has long been treasured in Protestantism. You could make a case that this doctrine is one of the key convictions that eventually gave birth to the Protestant Reformation. It is the belief in the fundamental clarity of scripture. The Bible is able to be clearly understood by all people (although Luther and especially Calvin would hasten to add that the Holy Spirit must be involved in the process of reading in order to overcome the reader’s sinful nature). The belief in perspicuity moved the locus of authority in interpretation away from sacred tradition and the Church to the individual interpreter. Now Protestants, and especially evangelical Protestants, simply assume that the individual reading scripture on her own is perfectly capable and even expected to understand, meditate upon, and apply that scripture to her life usually within the parameters of a “daily quiet time.”

This isn’t the place to debate the nuances of perspicuity. I accept a certain level of perspicuity as being in line with the original intent of scripture. I believe that scripture is not just for the elites but is for all people in all times and places. However, even champions of the doctrine like Luther clearly believed that not every individual reading of the text was equally correct. There was an essential role for an informed teaching ministry within the community of believers to correct and to train in the proper meaning of scripture.

The reason that I am mentioning this point now is because I have noticed that when it comes to dealing with difficult issues in the text the doctrine of perspicuity is sometimes abused. For instance, take the issue of women’s roles in ministry. This is clearly a difficult issue that the church has been struggling with for years. Exegetically there are a small number of texts in the New Testament that seem to prohibit certain roles for women within the assembly of believers (specifically 1 Cor. 14 and 1 Timothy 2). If we are to ever arrive at a principled position on the role of women in ministry today, these texts have to be studied and “figured out.” There are all sorts of exegetical questions that we have to answer:

- There are historical-cultural questions to be answered. Was there anything in the specific cultures of ancient Corinth and Ephesus that necessitated Paul’s restrictions on women in those churches? Further, was Paul articulating a general principle to be applied in every one of his churches (and therefore should also be applied in the same way in all of our churches) or was this simply a specific contextualization of a general principle (even the two major texts in question don’t agree on every detail)?

- There are important contextual questions to be answered. How do these restrictions fit within the context of the letters of 1 Corinthians and 1 Timothy? What was going on in these churches that would cause Paul to talk in this way? How do these restrictions fit within the broader context of the New Testament? For instance, what are we to make of Paul “tolerating” the teaching ministry of Priscilla and other prophetesses in Acts? What was Jesus’ own understanding of women disciples? How do these texts relate to the general principle of equality outlined by Paul in Galatians 3?

- There are important grammatical and semantic questions to be answered. What did Paul mean by “authority” or “head” or even “submissiveness?”

- There

are important questions of application as well. Why apply 1 Cor. 14 literally in

all churches today but not 1 Cor. 11 which talks about head covering for women?

Why permit women to lead worship through song or prayer if they are “not

permitted to speak?” At what point are women allowed to teach in the church?

Where did we get the idea that it was ok for them to teach boys until the sixth

grade but not after that point (as some churches practice)? Is it ok for women

to “teach” but not “preach” (even though the word for “preach” is nowhere used

by Paul but “teach” is in 1 Tim. 2)? We have to own up to the fact that our

application of these texts is laughably inconsistent.

If we are to take a stand on a difficult issue like women’s roles in ministry (or dozens of other similar issues), we must commit ourselves to understanding the word by doing the difficult work of exegesis.

Tuesday, May 21, 2013

More adventures in bad exegesis

One of the things that I like to do on this blog is to catalog examples of glaringly bad exegesis. Typically these examples come from the more "lunatic fringe" of biblical exegesis - sometimes from the far right and sometimes from the far left. It is striking to me just how often a really bad interpretation of the text can be directly traced in some way to political leanings on certain issues of government and society - whether it is the supposed emasculation of the American male (as in the famed "pisseth against the wall" video) or the more recent debate about same sex marriage (as in this case). Political agendas are often caustic to attempts at a faithful and humble reading of the text. So, behold the latest example here. What makes this example most alarming is that this is coming from a presiding bishop in a major Christian denomination who should have more common sense than this. She isn't just preaching to a small group of Christians in her living room. Her politicizing of the text is, in my mind, inexcusable but not altogether surprising.

Monday, May 20, 2013

How to take a stand on difficult issues (Part 1)

One of the things that we talk about every semester in my "Issues in Interpretation" class is how to take a stand on difficult issues of theology and hermeneutics. What are those principles and those virtues that should guide us when debating and conversing about contentious issues related to the Bible, culture, theology, etc.? Now that the semester is finally over, I am going to post over the next several days some of my own principles on how to take a stand on difficult issues. As usual, I welcome your comments.

1. Have I loved the person on the other side of this issue?

There is an Indian proverb that goes something like this: “There is no point in cutting off a person’s nose and then giving him a rose to smell.” Someone else said: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” The same person even said to love even your enemies. Jesus came into the world full of both grace and truth. It seems that the manner that he came into the world should be the same manner in which we try to conduct ourselves in the world. The second greatest commandment is not suspended the moment that we enter into a theological debate. This is not to mean that we shouldn’t have a position and defend that position with conviction. (To let a person continue in obvious error without any sort of confrontation may be “nice” and “tolerant,” but it certainly isn’t loving.) And there are some issues (more on this later) which demand a stronger, uncompromising defense. I am simply saying that in the midst of our debates we shouldn’t forget that there is another person on the other side of the debate who is deeply loved by God and should be deeply loved by us as well.

In other words, ask yourself what is the motivation for your debate? I’m worried about the Christian whose sole motivation is to win a debate. We imagine ourselves, like Saul of Tarsus, doing the Lord’s work with righteous zeal. If other people get offended or hurt or angry along the way, that is just the cost of doing battle for the Lord. We are God’s champions. But in the way that we conduct ourselves, we commit violence; violence against our neighbor and brother and ultimately violence against the purpose of Christ. So often what we are defending is not really God anyway. Because of our own insecurity, we end up defending only our own pride. Our theological positions become like idols that demand our devotion and our defense.

Be careful of disembodying your opponent on any difficult issue. We may be tempted to say, “It is the principle that matters. Nothing else.” This sounds a lot more righteous than it actually is. Remember, it was the Greeks who loved to argue about disembodied ideas (Acts 17?). Christian theology is embodied. People matter in the kingdom of God. But sometimes it seems that we love ideas so much more than people. People are messy. People are difficult. People take time. People require our service and our love. Ideas on the other hand are manageable. There is little selflessness in an idea. In fact, I can easily use an idea in my own service. Too often my ideas may seem to be about something else, but really they are about me.

We disembody our opponents in a number of ways. (One way might be in calling them “opponents.”) But one of the most common ways that we disembody others today is by engaging in debate through the safe anonymity of the Internet. The Internet has empowered us to say things to people online that we would never dream of saying to their face. The Internet has made slander convenient. Like a video game that allows us to virtually and safely fight all manner of enemies, the Internet has given us an arena in which to send our disembodied ideas into battle against other disembodied ideas. I’m not saying that we should never dialogue on-line, but we should probably develop the habit of asking ourselves whether or not I would say in person what I’ve just said on-line. If the answer is “no” then you are probably running the risk of disembodying your opponent. And let’s all just admit it. All of our verbal jousting on-line has paid very little actual benefit to the kingdom and in some cases has done a great deal of harm.

1. Have I loved the person on the other side of this issue?

There is an Indian proverb that goes something like this: “There is no point in cutting off a person’s nose and then giving him a rose to smell.” Someone else said: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” The same person even said to love even your enemies. Jesus came into the world full of both grace and truth. It seems that the manner that he came into the world should be the same manner in which we try to conduct ourselves in the world. The second greatest commandment is not suspended the moment that we enter into a theological debate. This is not to mean that we shouldn’t have a position and defend that position with conviction. (To let a person continue in obvious error without any sort of confrontation may be “nice” and “tolerant,” but it certainly isn’t loving.) And there are some issues (more on this later) which demand a stronger, uncompromising defense. I am simply saying that in the midst of our debates we shouldn’t forget that there is another person on the other side of the debate who is deeply loved by God and should be deeply loved by us as well.

In other words, ask yourself what is the motivation for your debate? I’m worried about the Christian whose sole motivation is to win a debate. We imagine ourselves, like Saul of Tarsus, doing the Lord’s work with righteous zeal. If other people get offended or hurt or angry along the way, that is just the cost of doing battle for the Lord. We are God’s champions. But in the way that we conduct ourselves, we commit violence; violence against our neighbor and brother and ultimately violence against the purpose of Christ. So often what we are defending is not really God anyway. Because of our own insecurity, we end up defending only our own pride. Our theological positions become like idols that demand our devotion and our defense.

Be careful of disembodying your opponent on any difficult issue. We may be tempted to say, “It is the principle that matters. Nothing else.” This sounds a lot more righteous than it actually is. Remember, it was the Greeks who loved to argue about disembodied ideas (Acts 17?). Christian theology is embodied. People matter in the kingdom of God. But sometimes it seems that we love ideas so much more than people. People are messy. People are difficult. People take time. People require our service and our love. Ideas on the other hand are manageable. There is little selflessness in an idea. In fact, I can easily use an idea in my own service. Too often my ideas may seem to be about something else, but really they are about me.

We disembody our opponents in a number of ways. (One way might be in calling them “opponents.”) But one of the most common ways that we disembody others today is by engaging in debate through the safe anonymity of the Internet. The Internet has empowered us to say things to people online that we would never dream of saying to their face. The Internet has made slander convenient. Like a video game that allows us to virtually and safely fight all manner of enemies, the Internet has given us an arena in which to send our disembodied ideas into battle against other disembodied ideas. I’m not saying that we should never dialogue on-line, but we should probably develop the habit of asking ourselves whether or not I would say in person what I’ve just said on-line. If the answer is “no” then you are probably running the risk of disembodying your opponent. And let’s all just admit it. All of our verbal jousting on-line has paid very little actual benefit to the kingdom and in some cases has done a great deal of harm.

Friday, March 29, 2013

Guest Post: A Former Student's Perspective on Homosexuality and the Church

I was contacted this week by a former student. I was priveleged to have this student in several classes during his years at OCC and we have remained in contact since his graduation. I have known about and we have talked about his struggles with homosexuality. He asked me if I would be willing to post his comments annonymously on my blog, and I agreed. I think that it is good, given the heat generated on social media this week, to hear from someone for whom this issue isn't abract or impersonal. He is a committed follower of Christ and passionate for the word of God and for holiness who also happens to struggle with homosexuality. I'm sure he isn't alone. I value his perspective. I also think it is appropriate to post this today - on Good Friday - a day we remember and celebrate each year as the day that all of our sins were atoned for by the blood of Jesus Christ. I offer his comments here without any further commentary.

I'm a graduate from OCC. I graduated in 2009 and since my graduation, I have been hired to lead two ministries and have started working on a Master's Degree in Christian Education.

Did I mention that I used to be involved with homosexuality?

Don't worry. This isn't a post where I am going to lay out an argument that the church need to change its stance on homosexuality because I know that is not God's will as laid out in Scripture. But what I want do to is tell you about my struggles with homosexuality and my life as a ministry leader. Before you post another rant on Facebook about the gay agenda or preach another sermon about homosexuality, I want you think about what you really believe about the sin.

I'm a graduate from OCC. I graduated in 2009 and since my graduation, I have been hired to lead two ministries and have started working on a Master's Degree in Christian Education.

Did I mention that I used to be involved with homosexuality?

Don't worry. This isn't a post where I am going to lay out an argument that the church need to change its stance on homosexuality because I know that is not God's will as laid out in Scripture. But what I want do to is tell you about my struggles with homosexuality and my life as a ministry leader. Before you post another rant on Facebook about the gay agenda or preach another sermon about homosexuality, I want you think about what you really believe about the sin.

Upon graduating college, I went on a search for a ministry position with great references. I was flown all over the country for interviews and was asked about my testimony. I was honest about my testimony. I let them know about my past and how I know I am forgiven that it is not a life I long to live. I long to serve Jesus Christ. That didn't matter. Instead, after giving my testimony, I would be asked questions like:

"Have you ever had any sexual contact with a child?" or "If we hire you, could you be able to keep that under wraps so as to not cause problems for our members?"

Eventually, I got hired but by churches that didn't ask for my testimony. When I did talk about my past, I would be told to not tell anybody unless I would risk being fired.

Eventually, I got hired but by churches that didn't ask for my testimony. When I did talk about my past, I would be told to not tell anybody unless I would risk being fired.

I hate that when I go to my local Target and see pictures of either a woman in her underwear or a man in his underwear, I have to look away from the man to fight the urge to lust. It's embarrassing and it's a constant reminder of my past. It's a struggle I have but for some reason, I can't talk about that struggle but we are okay with hearing about another person's struggle with alcohol or drugs or even heterosexual lust.

This week everybody is talking about gay marriage. Sadly, what will happen is the same: a preacher will talk about the Bible's views on homosexuality and then point out 1 Corinthians 5 in which Paul writes that the misdeeds are what we "were". Then the preacher will explain a homosexual can leave their life and that they weren't born that way.

I agree with this to an extent. I wasn't born to give my life to sin. I can't help the temptations, but I refrain from pursuing their desires, as difficult as it can be at times. But what breaks my heart is that even though this is what we preach, it is clearly not what we practice. As ministry leaders, we would rather the sin be murder than homosexuality.

I don't write this as a hate-filled argument for churches. My intent is for some mirror-holding. I hear your sermons. I see your Facebook posts. Yet, what is said in a pulpit isn't really lived out.

As a leader, would you hire a person who is redeemed from the life of homosexuality? What is your excuse to not do so?

As a leader, would you hire a person who is redeemed from the life of homosexuality? What is your excuse to not do so?

On a final note, why the silence? Why not let leaders who struggle with homosexuality (I know I'm not the only one) speak out? Wouldn't they be an excellent testimony?

Wednesday, March 27, 2013

Shades of things to come

At some point, I'd like to be able to dedicate a series of posts to the issues of homosexuality and same-sex marriage and the Church's response. As it is now, I simply don't have the time to give it the attention it deserves. I did want to share this article however. Regardless of your opinions on this opinion piece, this is a great example of how the debate is currently being framed. There is an unblinking equivocation - fair or unfair (I believe unfair) - between the issues of race and sexual orientation. Christians who believe that homosexual sex is a sinful behavior (as I do) should not be surprised when they are labelled as a bigot. "I love gays. I just don't endorse the lifestyle and I don't think that they should be allowed to marry. I'm not a bigot though. I love gay people!" But when the argument is being framed in already long established civil rights lines, you will be perceived as a bigot - regardless of your attitude. A nice racist is still a racist.

Opinion: Bigotry drags marriage back to Supreme Court - CNN.com

Opinion: Bigotry drags marriage back to Supreme Court - CNN.com

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Ugh

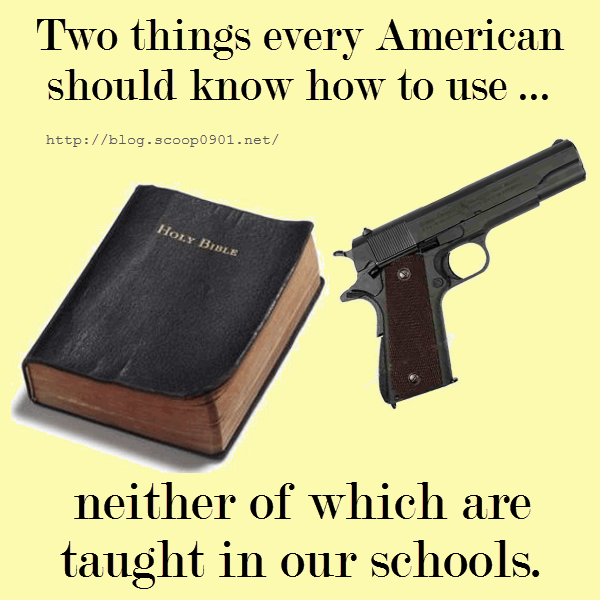

I'm very confused by this. Schools should offer training in biblical interpretation and fire arm usage? I am not a pacifist and I am not in principle opposed to Christians owning and using fire arms, but the naked equivocation of scripture and fire arms in this picture makes me a little nauseous. Add to it the inherent nationalism...and well....ugh. I've got serious questions about whether or not the creator of this actually does know how to use the Bible.

Friday, March 1, 2013

Gutenberg's Revolution

In 1455 all Europe's printed books could have been carried in a single wagon. Fifty years later, the titles ran to tens of thousands, the individual volumes to millions. Today, books pour off presses at the rate of 10,000 million a year. That's some 50 million tons of paper. Add in 8,000 to 9,000 daily newspapers, and the Sundays, and the magazines, and the figure rises to 130 million tons. (John Man, The Gutenberg Revolution, 4)One of the most underrated influences on biblical interpretation is the invention of the printing press. Most books on the history of hermeneutics leave a Gutenberg shaped hole in their study. One of our most treasured ideals as Evangelicals - personal, devotional study of scripture leading to a very personal and devotional relationship with Jesus - wasn't even the dream of a possibility before around 1455. Luther would never have become Luther, Calvin would never have become Calvin, and Tyndale would never have become Tyndale without this invention which John Man identifies as the third most important invention in civilization only after the inventions of writing and the alphabet. The Reformation probably wouldn't have happened without the assistance of the press. (Man points out that Muslim nations had access to the new technology but for multiple reasons they rejected it. And Christianity had a major reform movement while Islam did not. This is a simplistic analysis, but it's interesting to think about.)

The Internet is the fourth most important invention according to Man which ought to give all of us a pause. Just as the press allowed a new world to come into being, Internet technology is bringing another world into existence. The press undeniably changed the church and certain assumptions about discipleship. We can only assume that the Internet is having and will continue to have similar effects. The press changed the way that Christians interacted with the Word. Look around your church on Sunday morning and take note of all of the people with their noses buried in their phones and it is clear that Internet based technology is also changing the way that people interact with the Word. The question is "How?" And is it for the better or the worse? But I'll leave those questions to the Leonard Sweets of the world to figure out.

Monday, February 18, 2013

Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals

Just finished Slaves, Women, and Homosexuals by William Webb. The dominant purpose for the book is to provide some guidelines when making judgments about what is cultural and what is transcultural in scripture. In other words, how do we decide if a text in scripture is intended only for its immediate cultural context ("greet one another with a holy kiss") or if it is meant to be applied in every culture ("your sins are forgiven")? Some passages are relatively easy to categorize. Others are notoriously more difficult like Paul's comments about women in 1 Timothy. Webb's observation is that scripture teaches what he calls a multi-level ethic - not a simple static ethic. Scripture establishes a trajectory of faithful applications. We should apply the text differently as the culture changes. This isn't to strip scripture of its authority - quite the opposite. This gives scripture a contextual power whatever culture it may encounter. In a multi-level ethic the principle and the application of the text are related but different. In a static ethic, the principle and application are seen together. The application may need to be translated into a more contemporary culture, but the application is essentially the same.

Webb calls his approach a redemptive-movement hermeneutic. He uses the case of slavery to illustrate his approach. Scripture does not openly condemn slavery, but it does establish a sort of trajectory which eventually led committed Christians to challenge the institution of slavery from scripture itself. From this case study, he moves on to talk about the situation of women and homosexuals in scripture - two hot button issues in our culture today. In the case of women, Webb argues that the trajectory established by scripture moves from patriarchy to what he calls "complementary egalitarianism." The case with homosexuals is far different however. The trajectory established by scripture is not one of acceptance and endorsement but one of condemnation. You can see a summary of his position here.

I liked this book overall. I think that there were times that he seemed to be stacking the deck in favor of his already decided positions, but it is hard to argue with his observations and methodology. All of us engage in a multi-level ethical understanding of scripture - even those pious "literalists" among us.

Webb gives eighteen criteria from making judgments about what in scripture is culture and what is transcultural (or universal in application). I decided to reproduce them here. Some are more convincing than others, and he also discounted or ignored historical theology and the regula fidei in his approach (especially on the interpretation of various Pauline texts on women), but taken together they provide some nice guidlines in deciding these issues.

Persuasive Criteria (his designation):

1 - Preliminary Movement - A component of a text may be culturally bound if Scripture modifies the original cultural norms in such a way that suggests further movement is possible and even advantageous in a subsequent culture.

2 - Seed Ideas - A component of a text may be cultural if "seed ideas" are present within the rest of Scripture to suggest and encourage further movement on a particular subject.

3 - Breakouts - A component of a text may be culturally confined if the social norms reflected in that text are completely "broken out of" in other biblical texts.

4 - Purpose/Intent Statements - A component of a text may be culturally bound, if by practicing the text one no longer fulfills the text's original intent or purpose.

5 - Basis in Fall or Curse - A component of a text may by transcultural if its basis is rooted in the Fall of humanity or the curse.

Moderately Persuasive Criteria

6 - Basis in Original Creation, Section 1: Patterns - A component of a text may be transcultural if its basis is rooted in the original creation material.

7 - Basis in Original Creation, Section 2: Primogeniture - A component of a text may be transcultural, if it is rooted in the original creation material and, more specifically, its creative order.

8 - Basis in New Creation - A component of a text may be transcultural if it is rooted in new-creation material.

9 - Competing Options - A component of a text is more likely to be transcultural, if presented in a time and setting when other competing options existed in the broader cultures.

10 - Opposition to Original Culture - A component of a text is more likely to be transcultural if it counters or stands in opposition to the original culture.

11 - Closely Related Issues - A component of a text may be cultural if "closely related issues" to that text/issue are also themselves culturally bound.

12 - Penal Code - A prohibited or prescribed action within the text may be culturally bound (at least in its most concrete, nonabstracted form) if the penalty for violation is surprisingly light or not even mentioned. The less severe the penalty for a particular action, the more likely it is of having culturally bound components.

13 - Specific Instructions Versus General Principles - A component of a text may be culturally relative if its specific instructions appear to be at odds with the general principles of Scripture.

Inconclusive Criteria

14 - Basis in Theological Analogy - A component of a text may be transcultural if its basis is rooted in the character of God or Christ through theological analogy.

15 - Contextual Comparisons - A text or something within a text may be transcultural to the degree that other aspects in a specialized context, such as a list or grouping, are transcultural.

16 - Appeal to the Old Testament - A practice within a New Testament text may or may not be transcultural if appeal is (or could be) made to the Old Testament in support of that practice.

Persuasive Extrascriptural Criteria

17 - Pragmatic Basis Between Two Cultures - A component of a biblical imperative may be culturally relative if the pragmatic basis for the instruction cannot be sustained from one culture to another.

18 - Scientific and Social Scientific Evidence - A component of a text may be culturally confined if it is contrary to present-day scientific evidence.

Monday, February 4, 2013

The Bible in History

I just finished reading The Bible in History by David Kling. It is a very in-depth study of the historical importance of various key passages of scripture.

Chapter 1 explained the connection between Matthew 19:16-22 and the rise of the monastic movement.

Chapter 2 explained the rise of the papacy and the various passages - especially Matthew 16 which were sometimes used to justify the power of the Pope.

Chapter 3 talked about Bernard of Clairvaux and his allegorical interpretation of the Song of Songs which was the most frequently read and expounded book in the medieval monastery. Kling points out that nearly one hundred extant commentaries survive from the sixth to fifteenth centuries. More than 500 commentaries had been written by 1700 on this book!

Chapter 4 gave the history of the Protestant Reformation and talked about how various passages, especially Romans 1:16-17, were critical in the theological development of men like Luther.

Chapter 5 talked about the Anabaptist tradition which (eventually) took the various teachings of Jesus especially from the Sermon on the Mount on loving your enemy as critical to the practice of their faith.

Chapter 6 explained the influence of the Exodus story on the founding of this nation and in the development of African American theology as a protest theology.

Chapter 7 talked about the roots of Pentecostalism and the importance of the book of Acts in its origin.

Chapter 8 talked about the rise of feminist understandings of scripture rooted in such formative passages as Galatians 3:28.

The question that runs throughout the book is how do scripture and history interact. Do scriptural texts, pregnant with meaning and relevance, find their historical moment so that various passages actually change history? Or do the events of history actually change the sense of certain passages of scripture, so that texts are used or interpreted prejudicially to suit the historical needs of the moment? It's not an easy question to answer, and, like most things, the answer is probably both/and not either/or.

He does offer five conclusions at the end of his study which are worth sharing:

- Texts have indeed functioned as transforming agents. "Through Christian history, the Bible has functioned not merely as a book of story, instruction, and inspiration but as the vehicle of divine communication and supernatural transformation."

- Texts have also re-created meaning. "Texts of Scripture are not merely agents of transformation but are re-created and resuscitated int he interpretive and historical process. Texts re-create people, and people re-create texts. New ways of understanding are elicited by contexts. As a particular text works its way through history, it undergoes multiple interpretations and applications."

- Some select texts have served as comprehending sources. "A particular text of Scripture has functioned as a key text around which other texts of Scripture are illuminated, and these in turn refract back to the original text. Or to change the metaphor: a particular text functions as a centripetal force, drawing other biblical texts into its thematic orbit."

- Texts serve as hermeneutical keys. "A text functions not only as a comprehending source but also as an interpretive key to unlock the essential meaning of Scripture or resolve tensions within Scripture."

- Texts work as secondary justifications. "A particular text of Scripture functions to legitimize what has already occurred or to support the current climate of opinion. In a sense, many texts function in this way, for they confirm already existing notions, ideas, or convictions in the mind of the reader."

Fiorenza's Hermeneutical Authority

Schussler Fiorenza approaches the biblical text with a "hermeneutics of suspicion rather than with a hermeneutics of consent and affirmation." According to her feminist theory, "all texts are products of an androcentric patriarchal culture and history." Males not only wrote them but also have dominated their interpretation. Consequently, one must engage in a two-tier demythologization and "reclaim the Bible and early Christian history as women's beginnings and power." Because the text is the word of men, it is not authoritative and "cannot claim to be the revelatory Word of God." The Bible itself must be liberated from its "perpetuation and legitimization of such patriarchal oppression and forgetfulness of, silence about, or eradication of the memory of women's suffering."

Rather than appeal to a "canon within the canon"...Schussler Fiorenza calls for a "canon outside the canon." She proposes "that the revelatory canon for theological evaluation of biblical androcentric traditions and their subsequent interpretations cannot be derived from the Bible itself but can only be formulated in and through women's struggle for liberation from all patriarchal oppression." The New Testament is not the archetype--an ideal, unchanging, timeless pattern--but a prototype, an original, to be sure, but "critically open to the possibility of its own transformation." The text itself is no longer the interpretive authority; rather, the "personally and politically reflected experience of oppression and liberation must become the criterion of appropriateness for biblical interpretation and evaluation of biblical authority claims." The Bible "no longer functions as authoritative but as a resource for women's struggle for liberation."

In sum, "a feminist paradigm of critical interpretation is not based on a faithful adherence to biblical texts or obedient submission to biblical authority but on solidarity with women of the past and present whose life and struggles are touched by the role of the Bible in Western culture." Women's experience in their contemporary struggle against racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression is the standard by which to approach and interpret Scripture. Thus only those portions of Scripture "that transcend critically their patriarchal frameworks and allow for a vision of Christian women as historical and theological subjects and actors" are worthy to be considered divine revelation and truth.

from David Kling, The Bible in History (New York: Oxford, 2004), 302-303.

Rather than appeal to a "canon within the canon"...Schussler Fiorenza calls for a "canon outside the canon." She proposes "that the revelatory canon for theological evaluation of biblical androcentric traditions and their subsequent interpretations cannot be derived from the Bible itself but can only be formulated in and through women's struggle for liberation from all patriarchal oppression." The New Testament is not the archetype--an ideal, unchanging, timeless pattern--but a prototype, an original, to be sure, but "critically open to the possibility of its own transformation." The text itself is no longer the interpretive authority; rather, the "personally and politically reflected experience of oppression and liberation must become the criterion of appropriateness for biblical interpretation and evaluation of biblical authority claims." The Bible "no longer functions as authoritative but as a resource for women's struggle for liberation."

In sum, "a feminist paradigm of critical interpretation is not based on a faithful adherence to biblical texts or obedient submission to biblical authority but on solidarity with women of the past and present whose life and struggles are touched by the role of the Bible in Western culture." Women's experience in their contemporary struggle against racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression is the standard by which to approach and interpret Scripture. Thus only those portions of Scripture "that transcend critically their patriarchal frameworks and allow for a vision of Christian women as historical and theological subjects and actors" are worthy to be considered divine revelation and truth.

from David Kling, The Bible in History (New York: Oxford, 2004), 302-303.

Wednesday, January 30, 2013

Tertullian the Feminist